Subscriptions as price discrimination

2019-02-10

TLDR

- There are two types of subscriptions, those focused on the platform and those focused on the creators you’re supporting.

- Creator-focused subscriptions can be part of an extremely effective growth loop, with network effects and viewer lock-in.

- The most sophisticated subscription-based models are also the most efficient forms of price discrimination we’ve ever seen, where the subscriptions further the network effects and can both create and capture enormous amounts of value.

Price discrimination

I’m fascinated by business models which work, but oftentimes more interested in ones which didn’t work. I think of businesses as operating in two realms: one which creates value, and one which captures value — it’s clear that you need to do both to succeed.

The core insight here is that users value your product at some underlying price, and with more monetization paths you can more efficiently price discriminate. Some might value your service at $1 a month, some might value it at $100 per month, and some might not be willing to pay under any circumstances. In economic theory, the optimal price would be to figure out what each user’s willingness to pay is, and then charge them exactly that amount (MC=MR, shoutout AP Econ).

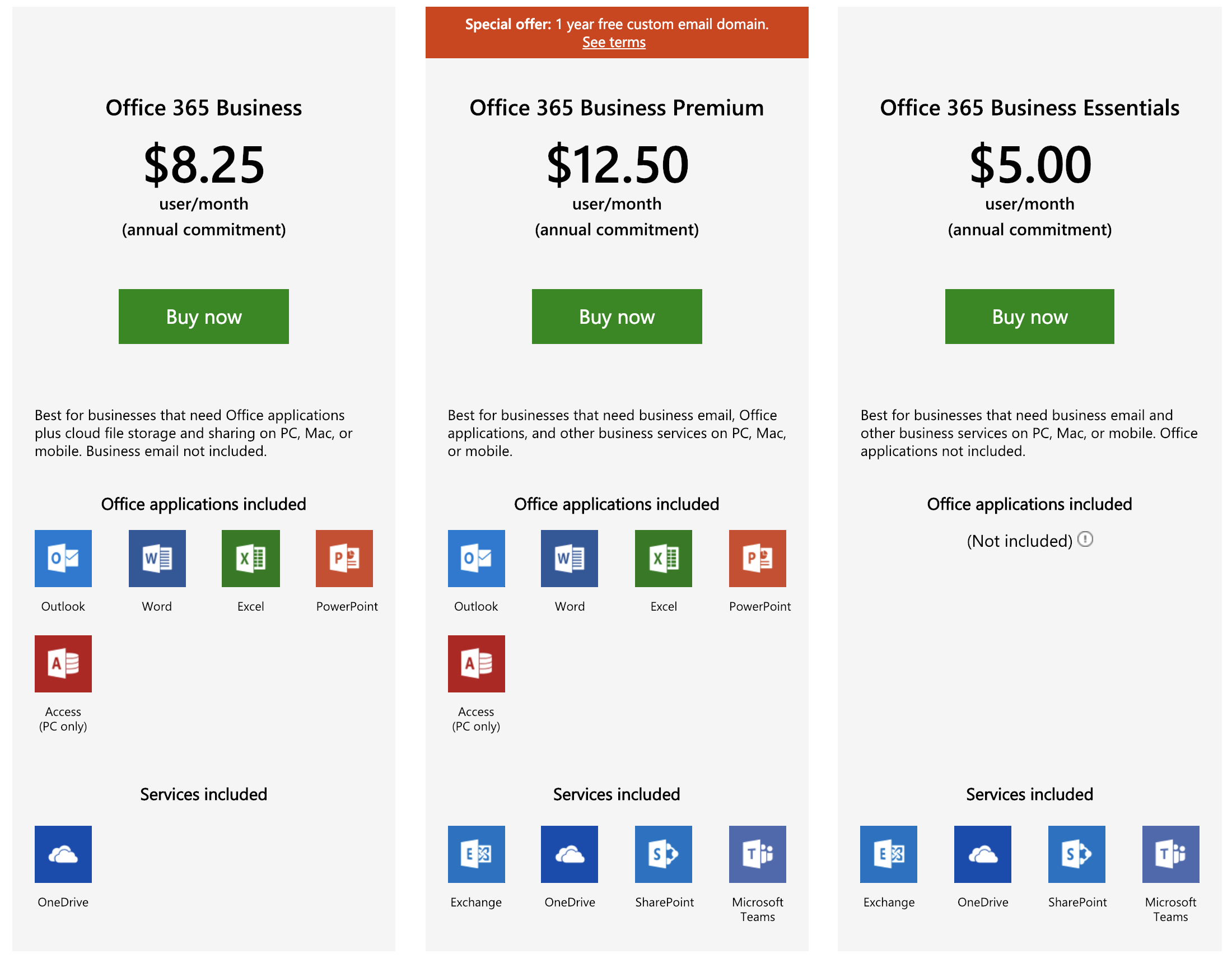

A canonical example of price discrimination is via software “suites” — the company’s already created the software, and it costs them basically nothing to give you other parts of the suite, but because different users are willing to pay different prices, they try to capture as much of the value that they create.

Does it cost Microsoft anything additional to “give” you the business premium suite versus the business suite? Probably not. In fact, old versions of Windows used to ship every CD as the fully upgraded “Ultimate” version, but with some additional code written to lock certain features unless an upgrade key was given — it took additional engineering resources to build the upgrade process, but it was worth it to capture more of the value they created.

In the internet era, two main models have emerged as ways to capture value, advertising and subscriptions. Older companies have primarily followed one path or the other (you can’t subscribe to remove ads on Facebook or Google Search), but more recently, companies are following what A16Z calls multimodal strategies, where they essentially leverage multiple monetization paths.

I don’t think that article is particularly actionable for most people —yes, WeChat doesn’t have to show many ads, but their parent was also worth almost $600B last year. Tencent is better understood as a conglomerate, which is defined by its diversification. Engineering resources are also much cheaper in China so it’s easier to throw bodies at building new features and trying to see what sticks.

A more actionable insight is that by combining subscriptions with advertising, it allows you to more efficiently price discriminate between users. No longer do you have to guess at how much value you’re creating, or hire McKinsey to figure out the right price for the right bundle — users will tell you!

Subscriptions within a network driven product

Subscriptions generally serve one purpose: for providers to earn money to provide services which customers pay them for.

Let’s differentiate here between two types of subscriptions:

- Subscriptions to the platform (e.g. LinkedIn Premium, Netflix, Spotify Premium)

- Subscriptions to creator-generated content (e.g. Patreon, Twitch, YouTube Gaming)

Subscriptions to platforms pretty much only serve the purpose of exchanging goods for services. However, subscriptions to user content allow consumers to show support for producer content.

This becomes especially clear within the context of a strong network: if you have two platforms with creators, and one of them lets consumers donate/subscribe to the creators, then consumers are actually incentivized to join the platform with donations and subscriptions, to be able to better show support. Obviously, creators are incentivized to join the platform which lets them monetize. I’d think that that platform both creates and captures more value and is better positioned for growth.

This growth loop is further amplified by the fact that you can price discriminate more efficiently between users now. Within a pure subscription setting, you’re missing out on the users who are not willing to pay much if anything at all for the service. Within a pure advertising setting, you’re earning relatively little per user and not extracting as much value from your heaviest users.

An interesting middle ground is traditional newspapers, which rely on both advertising and subscriptions. I would generally consider their subscriptions to be closer to a platform subscription, since you pay one fee for all of the content under a single masthead, rather than supporting individual journalists. It would actually be really interesting to see a platform dedicated to supporting individual journalists, especially given how precarious it can be to write for most traditional publications. With how ghoulish many publishers (and owners) have made themselves out to be, there is a real space available for a platform which focuses on supporting journalists, and solving distribution. I’m curious to hear if anyone has thoughts or is working in the space - dm’s are open.

In the wild

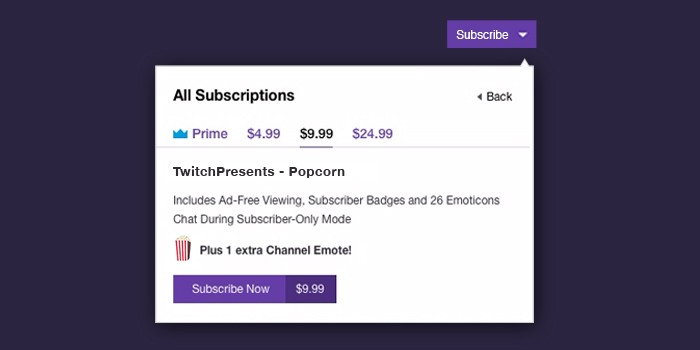

In the case of Twitch, lots of users won’t pay much to watch streams, but they can be monetized through ads (and I hear Amazon’s sales team is getting good), and people can also subscribe to individual people. Twitch’s real innovation here is that they don’t follow just a two level pricing model (ads + $5/month sub), but they built out more pricing levels to better capture how much users actually value supporting their subscribers.

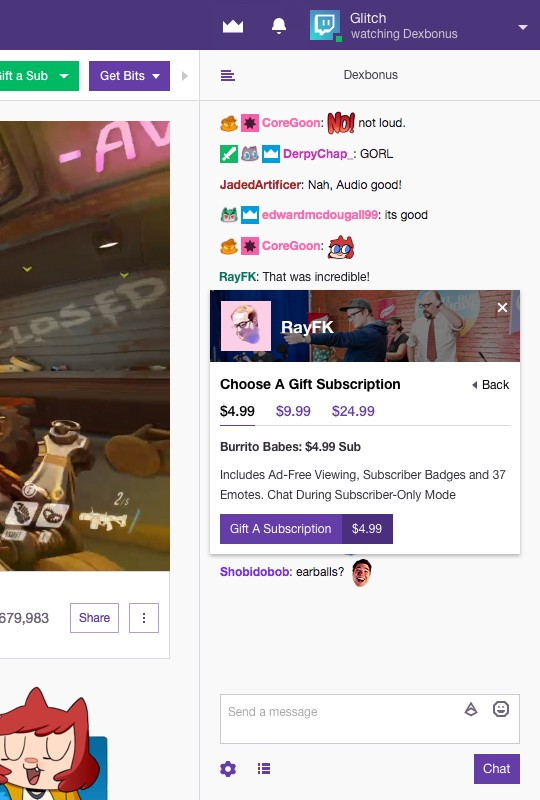

This is combined with the ability to gift subs:

This is a really efficient way to price discriminate, now: users can spend unlimited amounts supporting creators. Nobody would ever spend an unlimited amount on Microsoft Office, but they will when watching video games, if they value your product that heavily.

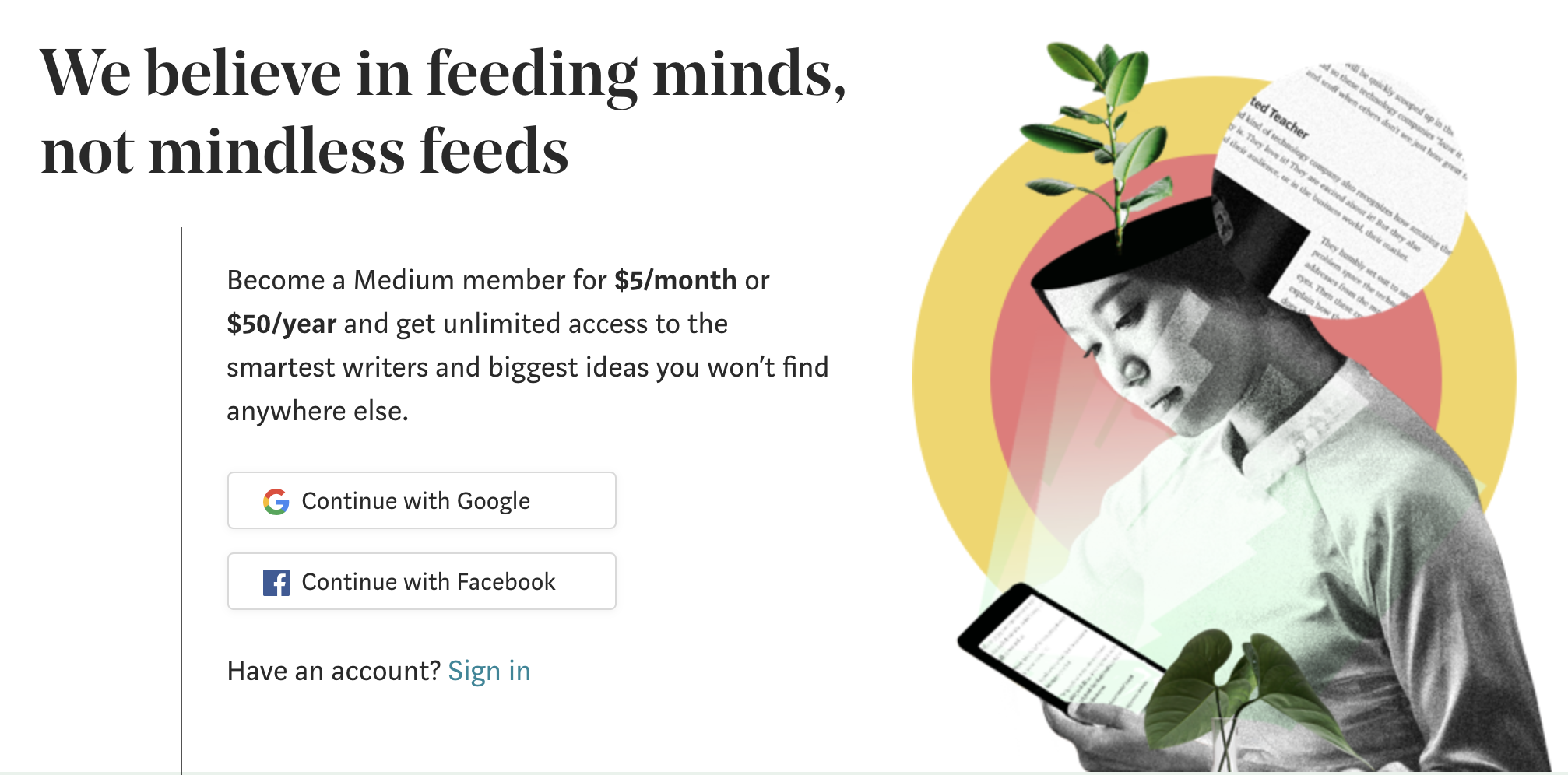

Contrast that versus Medium’s business model, which has no ads, but paywalls some content behind a Member paywall:

On the backend, the way their partner program works is that users’ membership fees are allocated proportionally to the writer based on how many articles the user read. Fine. Also there is something about clapping. I guess if I really like a writer I could make sure to read a lot of their articles so they can get some of that membership fee. But, as a consumer, I: a. can’t subscribe directly to the writer, and b. can’t signal that I value their content at more than $5 per month. No amount of claps can make up for that!

I am similarly pessimistic about platforms which try to offer “one fee for ad free access to all your favorite news sites” (e.g. Scroll) — the platform is not able to effectively price discriminate among their users and won’t be able to return that much money to the publishers.

A final observation: as somebody who spent hundreds on Patreon over the last year or so, I think Patreon will fail.

Patreon doesn’t provide a ton of value to creators; the core functionality is managing subscriptions and delivery of content to subscribers. This is reflected by the fact that Patreon only takes a 5% cut for themselves (they allocate about 5% to transaction costs, which in general, is roughly fair). I could build basically the equivalent over a weekend; there are plenty of other services for this niche, e.g. Memberful, which charges only $25 a month for a plan approximately equivalent to what Patreon offers. If you’re doing more than $500 a month on Patreon, you’d be better off on Memberful.

The fact that Patreon focuses on delivering content to subscribers, and not “anyone,” is one reason why they won’t succeed as a VC funded site. Content discovery is essential, which Patreon hasn’t invested in, and possibly couldn’t succeed in. Twitch is excellent at content discovery, and distribution to non-subscribers, in contrast. That’s a big part of why they can take a 50% cut of revenue — if Patreon tried to raise fees to that extent, they don’t have enough of a moat to keep users around.

Final strands

Supporting platforms vs creators is part of a broader theme which I think about: institutions vs individuals. That’s probably a worthwhile topic for a book, rather than a blog post, but it’s definitely timely.