Post-hyperscale

2019-04-21

Brought to you by the power of crowds.

Brought to you by the power of crowds.

Sandwiches and imperial warfare

When I studied abroad in Belgium, my favorite lunch spot was a small sandwich shop run by an affable old Tunisian man. He and his shop had almost legendary status among the exchange students; perhaps since he was one of the few who enjoyed speaking English, or was it the rumor that he was a TV chef in Italy? At any rate, he and I got along because I would always ask him for additional hot sauce on the sandwiches.

One day, I came in for my usual bolognese sandwich, and saw his face light up. “My friend! I have a special treat for you!” He had gone and found harissa, a staple of his childhood but not in Belgium, as “they can’t appreciate flavor.” This was something I saw over and over, that the Belgians would spice their beer (delicious!) but couldn’t bring themselves to put salt in their food. I didn’t understand this phenomenon at the time, but didn’t think that much of it, and instead subsisted on doner kebab.

It turns out that bland food is a tradition in Europe. Salt and spices used to be extremely rare and expensive; for salt, see “worth one’s salt”, for spices, see centuries of brutal colonialism. The rich of Europe were once willing to bring entire civilizations to their knees in order to sate their palates, so why would they no longer enjoy edible food?

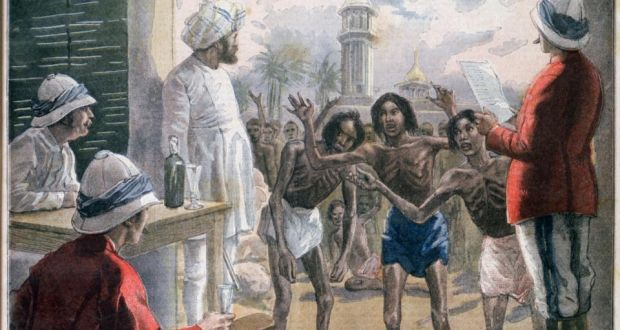

Starving Indians beg for food at a British Army post in 1897. Photograph: Getty Images

European haute cuisine once used lots of spices, because 1. they taste good, 2. they were expensive. But once enough spices started coming into Europe that any middle class schmoe could eat good, the rich were no longer able to signal wealth through their cooking.

“So the elite recoiled from the increasing popularity of spices. They moved on to an aesthetic theory of taste. Rather than infusing food with spice, they said things should taste like themselves. Meat should taste like meat, and anything you add only serves to intensify the existing flavors.” - Krishnendu Ray, an associate professor of food studies at New York University, as quoted by Maanvi Singh (2015).

The recoil from spiced food by elites when spiced food became commonplace is a prime example of countersignalling.

A brief literature review

It’s easy to highlight examples of countersignalling in daily life:

- The noveau riche enjoy showing their wealth off (sports cars, Gucci bags) but old money tends to signal wealth in less conspicuous ways, e.g. “charitable” foundations

- there is, of course, survivorship bias here :)

- Acquaintances show niceness by ignoring ones’ flaws, but the closest friends are the ones who roast you the hardest.

- People who went to average colleges love to say where they went, but Harvard grads will always say that they went to school in Cambridge.

- The best ramen restaurant in the Bay Area has an unmarked storefront and the door is painted as part of the wall.

(some adapted from Feltovich et al 2002)

I view these mechanisms as countersignalling at an individual level. In each of these, the person or entity countersignalling has some intrinsic property which truly differentiates themselves from others.

One explanation of why countersignalling arises hypothesizes that the countersignaller has less benefit from signaling than those without that intrinsic property or with less of that property. That is, if you went to Harvard, you don’t really need to broadcast that fact (though God knows some do) — you’ll always have your rolodex to call up, you’ll have it on your resume, etc. Nobody can take that away from you, the differentiating property really is intrinsic.

The European breakup with salt is a form of countersignalling, where the differentiating property is not intrinsic, but the rich still had less use for spices than others, as they could buy higher quality meats than others, even if the spices had the same utility. I’m most interested here by the fact that spices were once rare, and then one day they were not. There was a real increase in the standard of living (for many Europeans*), and yet, the rich chose to give up some of that increase to countersignal.

Status forgoing monkeys

In the most abstract form, the story was that object X was a reliable way to signal wealth, X was only available to certain people, X became available to everyone, forgoing X became the way to differentiate. Technology similarly removed many barriers to access or ownership. How do the rich differentiate themselves now?

- An iPhone XR costs under $40 a month, and for $10 more, you can get a top-of-the-line iPhone XS. That’s not that cheap, but it’s not a true status symbol anymore.

- The most culturally important websites — Google, Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, LinkedIn, among others — are all substantially free. If you don’t want to pay for Netflix or HBO or the movies, torrenting is very easy.

- Even within fashion, goods are much more accessible.

- Counterfeit streetwear is everywhere, and it looks the same, because they’re all mass-produced in China.

- Used luxury clothing is pretty generally accepted now, e.g. through Rent the Runway, Patagonia Worn Wear, or the dozens of other resale marketplaces.

For lots of people (in the developed world*), technology has made their lives immeasurably better and brought up the median standard of living, not just the top percentiles. In large part, these improvements came through hyperscaling. The more phones Apple produces, the more efficient and more cheap the next incremental phone is. The more users on Facebook or any social network, the more valuable the product.

But eventually the pendulum swings the other way, and you get articles like Human Contact Is Now a Luxury Good.

The rich do not live like this. The rich have grown afraid of screens. They want their children to play with blocks, and tech-free private schools are booming. Humans are more expensive, and rich people are willing and able to pay for them. Conspicuous human interaction — living without a phone for a day, quitting social networks and not answering email — has become a status symbol.

The fundamental phenomenon described here is countersignalling. We’re in the era of hyperscale, and it’s been good to most people, but the most elite are choosing to countersignal and withdraw from this portion of society.

So, with people who can afford to disconnect from the world in some way, or for those who aspire to disconnect, who will serve them?

Contact as a service

The logical and countersignalling conclusion to our hyper-optimized world are services which replace the efficiency of machines with the human touch. A few which are on top of my mind are:

- Superhuman is a $30/month frontend to Gmail (essentially), whose aim is to get you to Inbox Zero, which is itself a countersignal. What struck me about their onboarding and approach to customer support is that it’s all manual - somebody gets on a Zoom call with you and walks you through the interface and how you can use it. Coming from Gmail, there is a conspicuous lack of machine learning, and seems purposeful.

- Substack and Patreon are both platforms which allow creators to sell subscriptions to their content, and have came out against using recommendation systems to show content to potential new readers. I think that’s a poor decision (a subject for another post!) but it is an amazing piece of countersignalling. There are a few main things they’re signaling:

- Hey, you know Facebook? They use recommendation systems and feeds, so those are now bad, because Facebook. We’re not Facebook!

- If you’re on our platform, you have enough readers and followers that you won’t need further discovery. You yourself can countersignal — only those who are still seeking status need Twitter and other discovery mechanisms, if you have status already, Substack or Patreon can monetize it for you.

- There is infinite free content in the world, but we have premium content for sale. Countersignaling — if it’s not free, then it must be good!

- Amazon sells almost anything you could want with free 2 day shipping, and yet, boutiques and physical shopping are rising from the dead. Human curation and interaction are apparently worth the utility of not buying the same thing from Amazon as everyone else.

What other services would fall under this umbrella? What else will come next?

- Self driving cars might bring the cost of a ride down to nearly zero, but I’ll bet that rich people will still want chauffeurs, or failing that, Ubers driven by humans.

- Human curation instead of machine recommendation. Quite a few newsletters fall under this umbrella, but it can go so much farther than just that.

- High end restaurants with human interaction while servers at other places are replaced by tablets or counter pickup (looking at you, Souvla).

- What else? Sound off to me!

Crucially, these companies will not scale as well as those companies focused on machine learning or otherwise automating humans away. I don’t think they are particularly well-suited to venture capital since they will be more capital-intensive (humans are expensive) and have a smaller total addressable market (more expensive = fewer customers), but at the same time, enough people will be able to afford them.

The most successful will end up as their own status symbol, both for founders and customers. For founders, they can countersignal forgoing VC funding and unicorn status for a lifestyle business instead. For customers, they can countersignal the technological age with humans.

* - the plight and exploitation of the Global South subsidizes the wealth and living standards of the Global North. Please consider the implications of your actions on others and try to live ethically and sustainably. At a minimum, watch S3E11 of The Good Place.